Tradition is alive in the Grand Portage sugar bush

Although it was technically spring, winter was still hanging on this April morning in the Grand Portage sugar bush.

“Sap was frozen,” said Erik Redix, Ojibwe Language Coordinator for the Grand Portage Band. “It’s a very cold start. One of the coldest we’ve had in the years that I’ve coordinating the boil with Oshki [Ogimaag]. But that’s all right.”

Students from Oshki Ogimaag Community School, along with the school’s director and Ojibwe language teacher Cherie James, returned to the sugar bush to gather the frozen sap bags, which were thawed and added to the sap boil.

“This is something that ties us together as Anishinaabe people,” said James. “It’s a very important part of our culture. Today we’re spending the whole day here. There’s even been talk about actually camping and staying here at night. Because historically, that’s what the Anishinaabe would do. They would move there and stay for a few weeks until it was done.”

Redix agrees it’s good for the students to participate in all the steps and understand the amount of work required to make maple syrup. “The ratio is roughly 35 gallons of sap to a gallon of syrup,” said Redix. “Each one of them has a bag they decorated so they can see the output. Technology has sped it up a little bit. But, we’ve still got to be mindful of seeing the process through to the first week in May. That includes pulling the taps and not letting the sap go to waste.”

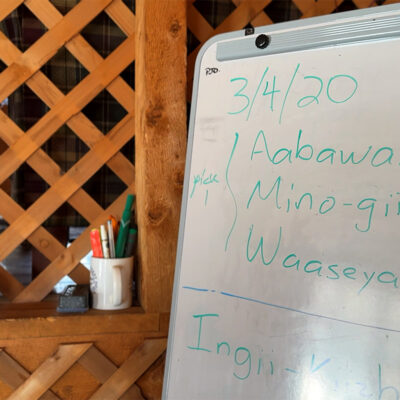

Learning Ojibwe language is integral to learning the sugar bush tradition. “I do a whole unit on Sugarbush,” said James. “I spend about three weeks on all Sugarbush related words and things that we do. We learn the traditional stories about how Anishinaabe people discovered maple sap. And then, of course, we come here.”

The combination of Ojibwe language classroom instruction with real-world sugar bush experience helps prepare students who may want to become fluent. “What I hope is, say we have 20 kids, four of them will go on to be fluent,” said James. “And that’s what we want in these programs. We want to revitalize the language.”

As the students learned how to make bannock – a traditional Ojibwe frybread – Erik Carlson was tending to the sap boil.

“I look around and there’s some of these folks that were brought out as teenagers or as little kids, and now their children are up here learning the same thing,” said Carlson, who is Lead Fire Technician for the Grand Portage Forestry Department.

“The important thing about culture is that, the root of anything that’s cultural is that it’s alive,” said Carlson. “It’s part of what the living people are actually doing. The kids are up here learning how to do it and bringing it forward.”

The family and community connection may be the most important part of the sugar bush experience.

“For me, what this day is about is a word, it’s called my relatives. It’s Indinawemaaganidag,” said James. “I’m related to half of the people here. And to come together and talk and laugh and have a good time, that’s really what it’s about. And to connect with the people that I love, my family. Indinawemaaganidag, that’s really what it’s about. Just that powerful connection today.”